4 Activists Who Make Me Proud to be Disabled and Transgender

As a disabled, transgender person, I don’t have a lot of role models. To understand what it means resist ableism and transphobia at the same time, I started researching the history of our community. Here are four disabled, transgender people in whom I take pride:

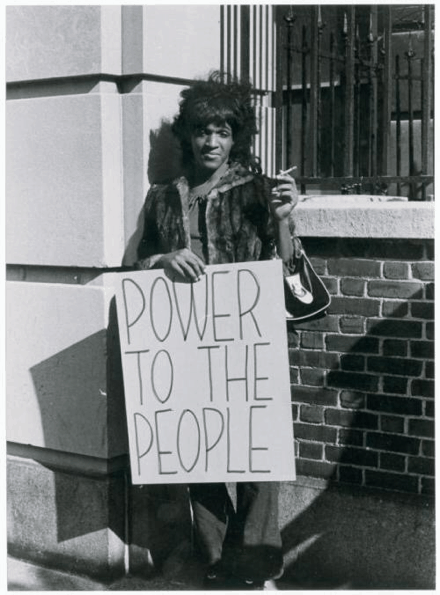

Few people are as important to transgender history as Marsha P. Johnson. Johnson was one of the first people to resist the police during the Stonewall Riots. She became key part of New York City transgender organizing. Johnson also had both psychiatric disabilities and physical disabilities. Because she was a disabled Black transgender woman, Johnson was regularly arrested and subjected to medical treatments without her consent. As a result, she developed a vision for liberation that addressed interlocking systems of oppression. In the documentary about her life “Pay it No Mind,” She quipped, “I may be cr*zy, but that don’t make me wrong.” Together with Puerto Rican transgender woman Sylvia Rivera, Johnson started Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), one of the first formal transgender organizations in New York City. STAR was a group by and for transgender young people who lived on the street, many of whom were women of color and disabled. Disability justice was at the center of STAR’s political analysis. They demanded that transgender people who were subjected to non-consensual psychiatric treatment be released from hospitals, calling them prisoners. Together with other NYC queer youth organizations, Johnson demanded that disabled people have free access to whatever therapy and medical resources they voluntarily chose, but also demanded that doctors must stop trying to cure their gender identity and sexualities. Instead, they argued that providers should understand how experiences of oppression cause disabilities. Johnson’s activism shows us that disabled people have helped to shape the analysis of queer and trans movements for decades. (Source: Cohen, Stephan. 2007. The Gay Liberation Youth Movement in New York: “An Army of Lovers Cannot Fail.” Routledge.)

Lou Sullivan was a white gay trans man at a time when doctors understood being gay and trans as contradictions. In 1975, he moved to San Francisco in hopes of obtaining treatment at one of the many gender clinics there. However, when Sullivan approached the clinic at Stanford University they denied his application because he was gay. This practice was widespread at the time. Doctors wanted their surgeries to produce healthy, employable, heterosexual citizens. Sullivan struggled to find a doctor who would give him the care he wanted desperately. His search led him to connect with other gay men, hoping to find resources and community. Eventually, he found a group of gay men with disabilities who embraced him. Sullivan came to understand his transgender embodiment as a disability. Later, he contracted HIV and often used a cane. His writing reflects a deep engagement with the disability politics. In fact, he was one of the first people to write about congressional attempts to restrict transgender people from claiming protection under the ADA. (Source: Smith, Brice. 2017. Lou Sullivan: Daring To Be a Man Among Men. Transgress Press.)

Bobbie Lea Bennett’s activism demonstrates just how much non-disabled transgender people owe to their disabled community members. Bennett was a wheel chair user from Louisiana. When she obtained gender affirmation surgery in 1978, she was told that the cost would be covered under Medicare’s Social Security disability benefits program. However, her payment was denied without explanation. Bennett mobilized the community around her case, forcing Medicare officials to consider whether or not gender affirmation surgeries were medical necessities. She drove all the way from her home in San Diego to the White House, eventually ending up that the Baltimore office of Medicare Director Thomas M. Tierney. She refused to leave until Tierney met with her and soon she received at check for $4600. Medicare officials denied that the money was to cover gender-affirmation surgery, but that didn’t change the significance of Bennett’s activism for disabled and transgender people. (Source: Matte, Nicholas. 2014. “Historicizing Liberal American Transnormativities: Medicine, Media, Activism, 1960-1990.” University of Toronto.)

Kay Ulanday Barrett is one of many disabled transgender activists who are working for justice today. Kay is a disabled queer and trans Pilipinx Amerikan poet, activist, and fashion icon. Barrett’s work discusses race, disability, diaspora, sexuality and their intersections. Barrett’s art powerfully demonstrates how systems of oppression reinforce each other. Their work also celebrates the resilience of all of the communities to which they belong. Their latest poetry collection, When the Chant Comes, is funny, sexy, heartbreaking, and inspiring.

Learning the history of disabled, transgender activism can help us to imagine new futures for our communities. Disabled transgender people are a part of a powerful legacy. We deserve to know about our past and take pride in it.

About Rooted In Rights

Rooted in Rights exists to amplify the perspectives of the disability community. Blog posts and storyteller videos that we publish and content we re-share on social media do not necessarily reflect the opinions or values of Rooted in Rights nor indicate an endorsement of a program or service by Rooted in Rights. We respect and aim to reflect the diversity of opinions and experiences of the disability community. Rooted in Rights seeks to highlight discussions, not direct them. Learn more about Rooted In Rights