How Do We Bring Social Justice to Special Education? With Love.

“What’s the Matter?”

[Child sobbing under his desk] “They said I killed the worms, but I swear I didn’t kill the worms!”

“Don’t worry, I believe you.”

“[Sniff] But they’re gonna tell the principal that I killed the worms!”

“That’s ok, because I will personally tell the principal that you did not kill the worms.”

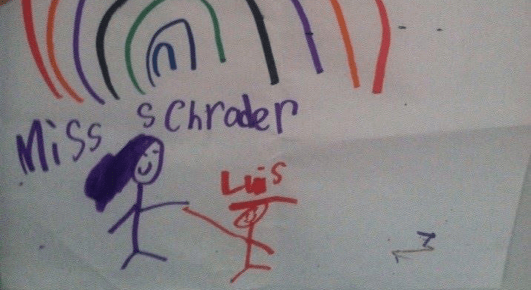

This was a conversation between me and a six-year-old child who I encountered in my first few weeks as a substitute teacher. The little boy had ADHD and likely struggled with feelings of being overwhelmed by his environment; moreover, he was rambunctious and had had some sort of altercation with other students in the class. The combination of these circumstances had overwhelmed him, and now he sat curled beneath his desk, crying. I had no idea what he was talking about, but whatever the situation was, it was clearly consuming his world. It was touching to see that once I’d reassured him, he calmed down. Later that day, he drew me a picture of the two of us holding hands beneath a rainbow.

Experiences like the one described above caused a critical shift in my perspective on how I could best improve the world. When I first began substitute teaching, I had been getting my feet wet in the burgeoning field of disability studies. As a person, I passionately concur with the Social Model of disability. The experiences I’d had growing up with a learning disorder taught me that the primary impediment to the well-being of disabled individuals is intolerance, not impairment. However, in the last few years, I’ve found that while the latter insight is brilliant, I have felt frustrated by the gnawing realization that the social model is a theory, not an intervention. Without a suitable application, my passion to help others felt lonely, ungrounded, and separate from the experience of love. In contrast, my work as a teacher represented the social model in practice.

As a person who grew up in Special Education, this realization was a bit of a retcon for me. From age eight until age seventeen, I had felt called to become a teacher. I loved people, I loved school, and I wanted to pass on the kindness of those teachers who treated me with respect and compassion. This all changed in high school, when I had to fight to take college preparatory courses and exams. Not completing these requirements could have kept me from attending college or even graduating, but the school didn’t care. As personnel put it, I was “not otherwise qualified” to do such things, and providing accommodations was “unduly burdensome” for them. During that same time, the Massachusetts legislature acceded to the teachers union and lowered its Maximum Feasible Benefit standard for Special Education to FAPE. I was so disgusted by these dynamics that I pursued degrees in cultural studies and musicology instead. I reasoned that there was no point in teaching third graders that they could do anything they wanted to in life if the school system and society were going to make those decisions for them.

Hence, I poured my desire to help the disabled community into academic research. I studied and published research on the history of the disability rights movement as it pertained to aesthetics, music, the horror genre and bioethics. I started lecturing in disability studies and advocated against assisted suicide at as many legislative hearings as possible, because I didn’t want other people to be manipulated by the same disempowerment that I’d experienced as a Special Education student. Nevertheless, I avoided engaging with Special Education directly, lest related resentment become my identity. Ironically, however, the topics that I did engage with made me intensely aware of horrible social dynamics that I couldn’t fix, and all I had to fight them with was righteous indignation. I hated these dynamics.

During my time as a substitute teacher, however, I realized that I loved my students-I was never happier than when a three-year-old boy with autism reached out to touch the soft fleece on the sleeve of my jacket, or when I purchased a stuffed kitten for an emotionally disabled preschooler. During these times, I experienced the strong sense that I was applying social justice theory to my interactions with people who needed justice the most. Hence, the contrast between those experiences taught me an important lesson about the difference between social justice theory and love. Unlike the uncaring darkness that I wanted to fight as an activist, teaching elicited a sense of warmth that I wanted to participate in. I realized that by making each child’s experience of learning safer, more inclusive and thereby richer, love had the potential to cut off social oppression at its root.

About Rooted In Rights

Rooted in Rights exists to amplify the perspectives of the disability community. Blog posts and storyteller videos that we publish and content we re-share on social media do not necessarily reflect the opinions or values of Rooted in Rights nor indicate an endorsement of a program or service by Rooted in Rights. We respect and aim to reflect the diversity of opinions and experiences of the disability community. Rooted in Rights seeks to highlight discussions, not direct them. Learn more about Rooted In Rights