India is home to more than 18 million blind people; most of us face stigma and discrimination on a day-to-day basis. Apart from inaccessibility and lack of awareness and funds, most blind people find it hard to get a good education or employment opportunities.

Not many among India’s blind population have the means to buy laptops and smartphones; nor do many of us have access to technology like screen reading software and apps like Audible. While there have been some free audiobooks and textbooks in braille, there hasn’t been anything much in English braille that the blind could read for leisure.

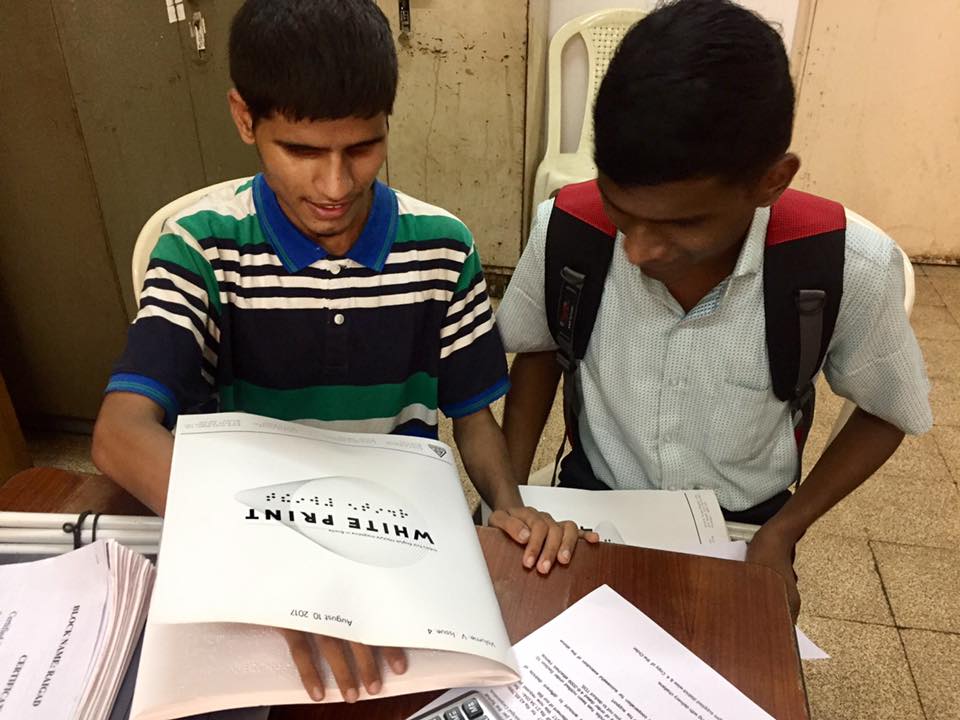

Upasana Makati, a former PR professional, loved reading the newspaper every morning. One day in 2012, she suddenly wondered what the blind in India read for leisure. After months of research and conversations with blind people, she realized that there wasn’t any Braille lifestyle magazine in English in India and decided to start one in 2013. The question she pondered was why shouldn’t the blind have access to leisure reading for fun like the sighted do. This was the beginning of White Print magazine, which celebrated 10 years of publishing in May of this year.

“It feels surreal to have completed a decade. I started at the age of 23 and, during this ten-year-long journey, I have found people who have told me this will not work even for a couple of years. When I spoke to advertisers initially, many people told me it’s not going to work for you. From that point to completing ten years now without being able to get any sort of massive investment and so, being bootstrapped, it feels phenomenal,” Makati says.

Due to a lack of funding, she often wrote the content herself and printed the magazine at her own cost at the braille press of the National Association of the Blind, in Mumbai. Printing a Braille magazine is expensive, too. For White Print, the cost of printing has risen from Rs 0.50 ($0.006) per page to Rs 3.00 ($0.036) in the last few years.

Although White Print had a few innovative brand collaborations in the past, post-pandemic advertising revenue has dwindled. However, Makati is determined to keep publishing the magazine because of the readers, some of whom have been reading White Print since its inception and look forward to it every month.

“Funding is still challenging and printing a Braille magazine is expensive and we’re charging only Rs 360 ($4.34) for twelve issues a year from our individual subscribers. Although some blind people have access to audiobooks, I feel blind people too should have the option to choose between reading a braille copy today and listening to an audiobook tomorrow. Just as sighted people have the option to choose between print, e-books, or audio,” she says.

For a long time, people with disabilities in India have been either seen as sources of inspiration or sympathized with. There is a lack of empathy and understanding. Makati still gets asked why she runs a braille magazine in this age of digital media. She feels this idea comes from a very ableist point of view and would then ask why the sighted still buy books or magazines!

Dr. Divya Bijur is a physiotherapist from Mumbai; she’s been blind since birth. She has been subscribing to White Print for the last seven years and finds the magazine insightful. Bijur feels White Print has helped her keep her connection with Braille. “I love reading Braille and have studied in Braille since the age of six. White Print covers diverse topics: from music, travel, parenting, nutrition, food, and environment to serious issues facing the world, and I think the work is great because we get to read various reading styles. The quiz is also amazing,” she says.

Although White Print is a lifestyle magazine, Bijur feels it encompasses her life by giving her a peek into the happenings of the world. “Reading generally cheers me up, and I feel ecstatic when I’m reading braille. White Print has been a great companion and at times I feel like throwing off my earphones and just being in peace and reading without sound, and that’s where braille comes to my rescue,” she adds.

Satish Nikam is a 75-year-old blind retired senior from the state of Maharashtra. He couldn’t study beyond ninth grade owing to trouble in arranging for scribes for his examinations and inaccessibility in general. However, he had always loved reading and learning new things. After working as a telephone operator at a sugar mill for many years, he retired in 2008.

“I have been reading White Print since it started publishing in 2013. I receive a monthly pension of Rs 900 ($10.81) only and do odd jobs even at this age to sustain myself and my wife. I often couldn’t pay for other materials in braille because printing in braille is expensive. I subscribe to White Print magazine and requested Ms. Makati to let me pay the subscription in installments or consider a concessional rate. Knowing the situation, Ms. Makati hasn’t charged me anything for all these years. The magazine carries articles on a variety of topics and opens up the world for a blind person like me. Although my English is not very great, I have learned a lot from White Print. There are articles on gardening, travel and culture, and so much more. And it gives us, the readers, a different kind of energy and joy,” he says.

White Print currently has a reader base of 10,000 blind people. Makati feels braille literacy is important for the blind even though many of them are increasingly learning the use of screen readers. “Sighted children are still taught with physical books and taught how to write in cursive or write using pencil and paper,” she adds.

Before the pandemic, Makati had collaborated with several brands to create interesting braille advertisements for the magazine. As advertising is mostly visual and depends a lot on color schemes, design, photography, and infographics, it was something completely new and creative for the brands to think of advertising in Braille.

“Raymond was the first company that we collaborated with. In October 2013, we had Coca-Cola advertise with us. They inserted an audio ad in the magazine which played a jingle as the magazine was opened. This musical card-like ad was very exciting for the readers as well because they felt a brand had done something specifically for them,” Makati says.

Sandesh Bhingarde is the founder of a Mumbai-based nonprofit organization called Team Vision Foundation. This voluntary organization works towards empowering visually impaired students in different ways and conducts blindness sensitization workshops.

“We have been subscribing to White Print magazine for more than a year and a half now. I feel the braille magazine is important because while working with the visually impaired, we’ve found they are missing out on reading and writing. We encourage the students to read in braille because, in many instances, blind students don’t know the spellings of words because they absolutely miss out on reading,” Bhingarde says.

While there are a few braille magazines in other Indian languages, there was a lack of Braille magazines in English. Students who use screen readers or use text-to-speech and autocorrect are improving their spelling by reading White Print, Bhingarde feels.

As White Print has entered its eleventh year of publication this year, Makati wants to spread the pleasure of leisure reading through braille literacy among a bigger number of blind Indians.

Just as every sighted child begins their schooling with pen and paper, braille as a script does the same for the blind. If a blind person does not have access to leisure reading via braille literature, their education and growth remain incomplete. Although screen readers like JAWS or NVDA have made it possible for the visually impaired to read, write and access the internet, braille remains the first step towards literacy for the blind. White Print has been trying to bridge the huge gap in the availability and accessibility in braille literature in India for more than ten years; I feel this is an important step towards enriching the lives of the blind in India.

Arundhati Nath (she/her) is a visually impaired independent journalist, content writer, and children’s author from Guwahati, India. Her work has been published in The Guardian, BBC News, Al Jazeera, CSMonitor, and many others. She can be reached at natharundhati@gmail.com and her published work can be viewed on her website.